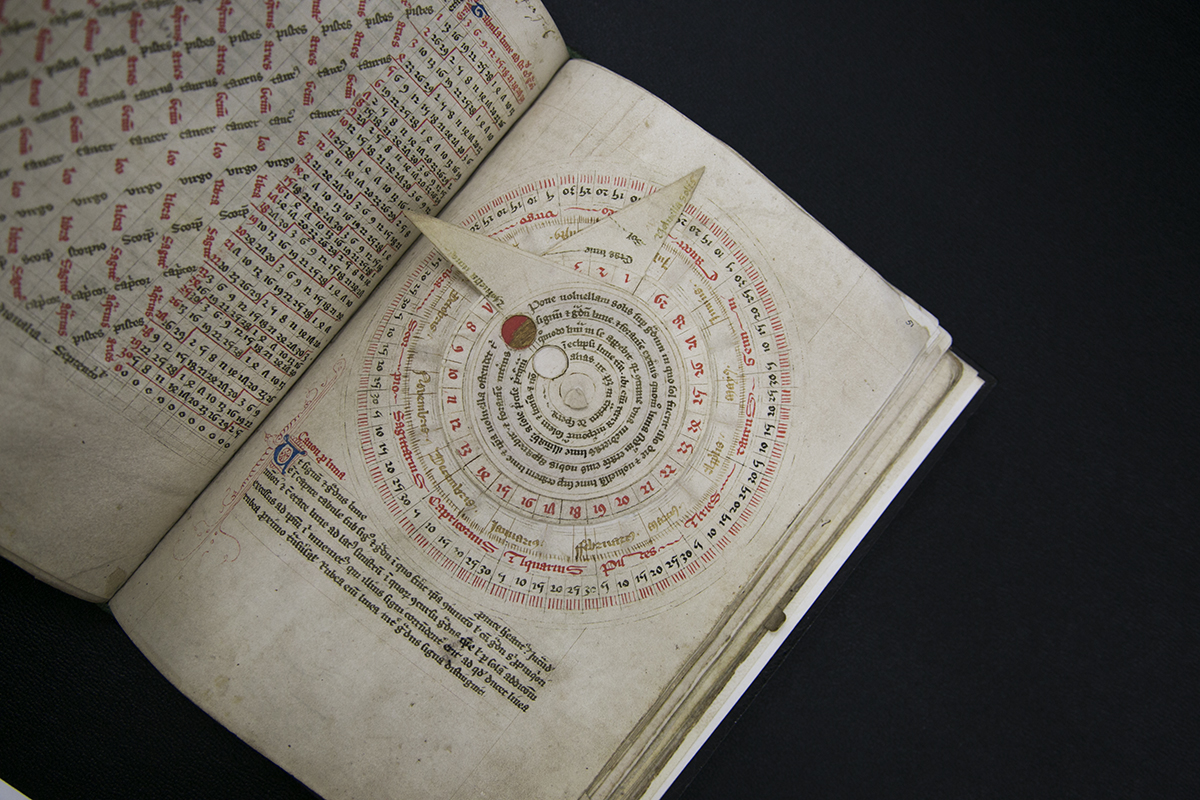

Astronomical Vovelle, from Astronomical and Medical Miscellany, English, late fourteenth century, shortly after 1386. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XII 7, fol. 51

One of the many enticingly tactile manuscripts included in the exhibition Touching the Past: The Hand in the Medieval Book, curated by former Getty graduate intern Megan McNamee, is a device called a volvelle.

Zooming in on the device here is almost as satisfying as touching the real thing.

Here’s how it works: Layered circles of parchment are held together at the center by a tie, allowing the user to rotate pointers to calculate the position of the sun (Solis) and moon (Luna) at different points throughout the year. A circle with letters in red also indicates the astrological sign associated with each period.

A volvelle is a cousin of the astrolabe. Volvelles are concentric paper or parchment circles used in medieval Europe to calculate the phases of the sun and moon, while astrolabes are instruments, often made of metal, used since antiquity to observe and calculate the position of celestial bodies.

(Aside on etymology: Volvelle comes from the Latin verb volvere, to turn. It is occasionally seen spelled as vovelle, while its moving parts are sometimes referred to as rundells.)

Ramón Llull as depicted by an unknown printmaker. Collection: Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Libraries. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

It is remarkable that this device—which inspires so much manipulation and movement—has remained intact since its creation around 1386. This was not long after volvelles were introduced to Europe in 1274 by artist and writer Ramón Llull, who worked in the Kingdom of Majorca (present-day Spain).

Llull was a mystic philosopher (with a wicked mustache) who hoped to settle religious disputes with his first volvelle, which produced combinations of nine letters thought to represent the nine names of God. Another volvelle by Llull called “The Night Sphere” used the position of stars to calculate time during the dark hours of the night. This allowed him to suggest the most “potent” times to administer medicine according to the movement of celestial bodies.

Diagram of an astrolabe designed by Llull. reproduced from Selected Works of Ramón Llull (1232–1316), edited and translated by Anthony Bonner (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985)

Determining time at night was achieved through the not-so-simple process of aligning the device with a pole star; closing one eye; centering the cross of circles on the face, equidistant from both eyes; and locating another star rotating around the central star. So long as you don’t move your head or hands in the least, you could determine your place in the universe!

Revolutionary for its time, the parchment calculating device was considered a form of “artificial memory” that freed users from committing large amounts of detailed information to mind. Because of this, the device has been compared to early computers—though a comparison to a floppy disk might be more accurate. In fact, more durable tools known as astrolabes had been cast in metal in ancient Greece, and the technology was preserved in the Islamic world before returning to popular use in Europe.

Astrolabe, Islamic, 15.6 centimeters. The British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum

However, as with any new technology, there were skeptics. Volvelles and their users were often suspected of dark magic, perhaps because of their mystical origins and their claims to predict the future. Even into the sixteenth century, numbers and measurements were given spiritual significance and supernatural potential. The eccentric individuals making use of the “secret” knowledge contained in such devices were often suspected of insidious intent. However, as scientific thought progressed, volvelles became increasingly valued not just for their ability to record information, but also for their potential to produce new knowledge.

As visitors to the volvelle currently on view may notice, access to these temptingly tactile devices often proves difficult. The high cost to produce the parchment of the volvelle in the Touching the Past exhibition limited its audience in the fourteenth century to the wealthy, scholarly elite. By the sixteenth century, advances in print technology made paper volvelles and other devices with movable parts available to a wider audience. However, the delicate pieces of paper and parchment are easily damaged or lost, relegating the delightfully movable devices behind museum glass and into rare book libraries in the twenty-first century.

A volvelle printed in a 1564 edition of Peter Apian’s “Cosmographia,” a work on astronomy and navigation, housed in the Getty Research Institute.

Fascinating (and fun).

Looks like a pregnancy wheel.

This is fascinating and I would like to see more information like this.

Hello, I’m Rheagan Martin, author of the post and curatorial assistant in the Getty’s Department of Manuscripts. Thank you for your interest and comments!

Howard makes a great point about the pregnancy wheel. In fact, the volvelle lives on in many modern forms such as star gazing charts, color wheels, and even tools to help conjugate verbs in foreign languages! For other fascinating modern examples I would suggest reading “Reinventing the Wheel” by Jessica Helfand published with Princeton Architectural Press in 2002.

For more on historic volvelles, you might get your hands on “Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge” the catalogue of an exhibition that took place at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art (Harvard Art Museums) in 2011, edited by Susan Dackerman.

Thanks for enlightening us on the volvelle; this is the first I have heard the term or books of this type.

I’ve worked quite a bit on volvelles as a rare book conservator, and find them so wonderful! A fun book to check out is “Reinventing the Wheel” by Jessica Helfand.

http://www.amazon.com/Reinventing-Wheel-Jessica-Helfand/dp/1568985967

I’m always looking for the earliest example of a volvelle and have never determined who made one first; was it Ramón Llull or Matthew Paris in his Chronica majora? Please let me know if you can.

The volvelle is very much like the concept of aligning text through the page in a book to convey a secret message. As you can see in the final diagram in this article, the text from the reverse side of the page is quite legible. I know that books were designed with transparent pages to align text or layers of an object to be able to peel away the layers, by turning the pages, to reveal the makeup of an object, but have you ever heard of this being done in a normal printing process? In the sense of printing in a book: “Who will believe my verse in time to come?”, while on the reverse side of the page, aligned with the word ‘time’, are the words ‘thou wilt’. In time to come is literal in that one must read on to turn the page to find the answer.

I’ve just come across this post: I’m sure the exhibition was fascinating. Lovely images and links in this piece, and very informative. You might be interested in a post I published a year before this, July 2014, which covered some of the same ground, and also considered ‘ars combinatorial’, the Lagado device in Gulliver’s Travels, and other related topics. Link here:

http://tredynasdays.co.uk/2014/07/volvelles/

I’ll update my 2014 piece with a link to this post.

Thank you for reproducing an image from Vol. II pf my book, but that’s not a volvelle: it’s an astrolabe, whose parts don’t move. Llull does use volvelles, but they’re in Vol. I. Where you got the date of 1302 is a bit of a mystery; The first work in which he proposes a volvelle (one of those in Vol. I) dates from ca. 1274. Nor do I understand what you’re referring to with the “wicked moustache”. Are you referring to the speech scroll coming out of his mouth. And why a silly 17th-century engraving which makes him look like a magus, when there are such beautiful medieval images of him, such as this one of him and his disciple (the chubby fellow kneeling) presenting three books of his to the queen of France: https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbhs/content/pageview/105563. Lastly, I’m not sure his volvelles weren’t predated by Arabic astrological diagrams, where they were ideal for depicting coincidences of stars and constellations.